E M Forster's Gay Fiction

This article was commissioned by the British Library for their Discovering Literature project. The original article can be found here.

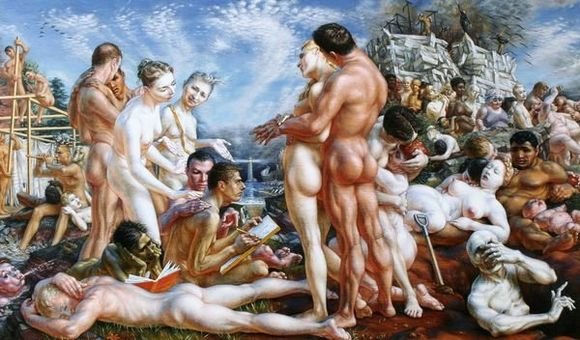

'What I Believe', by Paul Cadmus, featuring Forster

The last novel that E M Forster published in his lifetime was A Passage to India. That was in 1924. But Forster lived until 1970, so for the last 37 years of his life he published no more fiction, preferring to write essays instead. His creative silence both baffled and disappointed his readers: why had this popular, accomplished author (of five novels and numerous short stories) turned away from literature?

After his death, Forster’s reasons for reticence came into focus. In a diary entry of 1964, he reflected that ‘I should have been a more famous writer if I had written or rather published more, but sex has prevented the latter’. His wording here is key. At King’s College Cambridge, Forster had left behind a hoard of unpublished material, including a wealth of unseen fiction: a novel, two substantial fragments, stories, plays, poems. He might not have published any more fiction in the years since A Passage, but he had been writing. It is the subject of those stories, however, that kept them hidden. Forster hadn’t been writing about ‘sex’ in the broad sense of the word, but, more specifically, the ‘sex’ which meant something to him: sex and love between men.

A weariness of the ordinary

In 1895, when Forster was 16, Oscar Wilde was sensationally sentenced to two years of hard labour (the maximum sentence) for homosexual acts. As well as cementing the unacceptability of homosexuality in the popular consciousness, the imprisonment of London’s most famous and loved author read like a cautionary tale to Forster, casting a long shadow over his sexual maturation and identity. He kept his sexuality as covert as possible and wrote novels and stories about (to borrow his words) ‘ordinary people’, and ‘the only subject that I can and may treat – the love of men for women and vice versa’. But by 1911, Forster recorded in his diary that he’d grown weary of that conventional, oh-so-English, halcyon-idyll that governed his stories, and a reluctance to romanticise about the familiar subject set in. Just before the publication of A Passage to India, he wrote to the poet Siegfried Sassoon declaring that ‘I shall never write another novel after it – my patience with ordinary people has given out. But I shall go on writing. I don’t feel any decline in my “powers”’. It was not that he could not write anymore; it was that he would not write about a subject that he could no longer connect to.

Maurice was born out of a trip in 1913 to the poet Edward Carpenter, who Forster admired as ‘a believer in the Love of Comrades’ (or ‘Uranians’, as Carpenter said), and regarded as a ‘saviour’ in his particular moment of loneliness. During this visit, George Merrill (Carpenter’s much younger lover) touched Forster gently on the backside. The effect of this moment of connection was, Forster recorded, ‘as much psychological as physical. It seemed to go straight through the small of my back into my ideas, without involving any thoughts’. It was in that ‘precise moment’ that Forster mystically conceived of writing a love story between men. After completing a first draft by 1914, Forster tentatively showed the novel to select friends, and continued to do so over the forthcoming decades, reworking it as time passed. Christopher Isherwood, an openly gay novelist over 20 years his junior, saw the draft in its various forms on a few occasions, and repeatedly implored Forster to publish it. But Forster would not relent. Despite the passing of time and of individuals (to whom he felt the revelation of his homosexuality would hurt most), Forster believed there had been no profound progression since the days of Wilde’s conviction, and thought that public attitudes had only incrementally shifted, from ‘ignorance and terror to familiarity and contempt’. Instead, he bequeathed the manuscript of Maurice to Isherwood, and, a year after his death, the love story closest to Forster’s heart was published.

The reception of Forster’s gay literature

The initial response to the publication of Forster’s gay literature was mixed, and often negative. For some, Maurice was a blight on Forster’s otherwise unblemished literary record. The critic Francis King, who was a friend of Forster’s in his later life, avoided any full discussion of it in his 1978 book on Forster and his World, dismissing it as ‘the least satisfactory of all Forster’s novels’. Likewise, in 1976 John Sayre Martin described Maurice as ‘the least resonant of Forster’s six novels’. Even 12 years after it was published, Christopher Gillie declared in A Preface to Forster (1983) that ‘as a contribution to his reputation, Maurice was not worth publication’. Sadly it seems that Forster also questioned the artistic merit of this novel and his homosexually charged short stories. He burned a lot of the material, dismissing it as ‘sexy stories’ and a distraction from his art, and, on the cover of the 1960 typescript of Maurice that he’d left to Isherwood he wrote: ‘Publishable – but worth it?’

For some readers and critics of his earlier works, his literary and posthumous ‘coming out’ troubled their understanding of him. As Isherwood remarked of Forster’s heterosexual literature, ‘of course all of those books have got to be rewritten. Unless you start with the fact that he was homosexual, nothing’s any good at all’. The retrospective knowledge of Forster’s homosexuality has certainly led literary critics to revise their readings of the novels published during his lifetime, and has ‘queered the lens’ through which many of them look. As laws and attitudes towards homosexuality have become more positive, and Queer Studies have flourished, his gay literature has gone from being anomalous to pioneering, from being ignored to celebrated.

This new lens has deeply enriched our understanding of his heterosexual literature too. Critics have often criticised Forster’s depiction of romance between men and women as lukewarm, implausible even. Of Howards End, Katherine Mansfield wryly wondered ‘whether Helen was got with child by Leonard Bast or by his fateful forgotten umbrella. All things considered, I think it must have been the umbrella’. The unlikely pairing of Leonard and Helen, however, strains against Edwardian conventions, in what is possibly an earlier example of Forster’s dissatisfaction with the social strictures placed upon himself and his writing. ‘How annoyed I am with Society,’ fumed an elderly Forster, ‘for wasting my time by making homosexuality criminal. The subterfuges, the self-consciousness that might have been avoided’. Other relationships in Forster’s earlier fiction, like Lucy and George (in A Room with a View), transgress the usual rigidity of class structure. Whilst they might strike the reader as a good match romantically, their class difference does not qualify them as a ‘good match’ by Edwardian social standards. Even in his depiction of heterosexual relationships, then, Forster probed and challenged the normative boundaries of Edwardian romance.

‘The love that dare not speak its name’

In a poem (quoted in evidence against Wilde in his trial), Lord Alfred Douglas called the love between two men ‘the love that dare not speak its name’. In the context of a society where homosexuality was unconscionable, there was no language or pre-existing form in literature with which to express this type of relationship. Part of the challenge for Forster in writing this new genre of fiction was to find the words and create a world where this type of relationship could be realised.

His gay short stories are infused with the fantastical and the mythical – past lives, phantasmagoria, transfiguration are muddled into the ordinary. Forster once wrote that ‘I like that idea of fantasy, of muddling up the actual and impossible until the reader isn’t sure which is which’. By blurring the lines between fantasy and reality, Forster breaks down the barriers of the possible, making the impossible – homosexual relationships in the context of society – seem a little more attainable. Not only that, but it lightens them with whimsy and the sense of humour that was central to Forster’s sense of the world.

In Maurice, the play of colliding opposites – light and dark, public and private, the real and the dreamt – are crucial for achieving the happy ending that, for Forster, was imperative. In his struggle to come to terms with his homosexuality, Maurice is caught between his public and private self, and is at his most tormented in this twilight, liminal state. For the story of Maurice’s and Alec’s love to work, Forster felt that ‘Alec must loom out of nothing until he is everything’. It is in the context of darkness that Maurice finds his longed-for friend, and, choosing a life together, they disappear into ‘essential night’, to ‘live outside class’, outside of structure, convention, artifice, outside of the ‘stuffy little boxes’ that house society’s millions of ordinary people, and in the wide open spaces of England. In the parameter-less, unfathomable darkness Maurice and Alec are granted the freedom to live out their love, and Forster finds an image and situation for realising his happy ending.